People always ask me if the book is real—the old brewing log that, according to legend, was discovered hidden inside a wall at Pivovar Kout na Šumavě, and which contains the secret recipe that supposedly accounts for the magical taste of Kout Lagers. And if they haven’t tried Kout yet, they also usually want to know if the beers really are as delicious as I claimed they were.

Lately I’ve been telling them I’m not sure in either case.

They ask because I wrote a 16,000-word essay about Pivovar Kout na Šumavě in which I tried to uncover the brewery’s secrets. (And I say this in all honesty: I failed.) After falling in love with Kout’s two extremely charismatic and rather hoppy Pale Lagers, as well as its two rich and mysterious Dark Lagers, I traveled out to the brewery in remote western Bohemia three times in an attempt to see the brewing book of legend with my own eyes and find out more about the place.

The first time I went out there on vacation with my family. The second time I went to film a spot with Anthony Bourdain for No Reservations, during which I fell through a hole in the floor of the ruined old malthouse and nearly broke my leg. The next time I went out during a blizzard. I never actually got to see the old brewing book, and after that last trip I swore to myself I’d never go out to Kout na Šumavě again. The longform essay I wrote ends with that third visit, and when I finished writing it I thought I was done trying to uncover the secrets of Pivovar Kout na Šumavě for good.

And yet, a year or so later, I found myself heading out there again.

There’s certainly something special about the location: pronounced roughly like “coat nah shoe-ma-vyeh,” the old Bohemian village of Kout na Šumavě takes its name from the Šumava forest, a remnant of the quasi-mythological Hercynia Silva forest mentioned by writers like Ptolomy and Aristotle. Julius Caesar wrote that this forest was filled with unicorns, wild bulls, and giant elk with no knees. Pliny the Elder—way before there was a beer named after him—said it was home to strange birds whose feathers glow at night like fire.

Beyond the forest legends, the brewery has its own weird stories: its lagering cellars were carved underneath a church where a blind beggar foretold the future to Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia Charles IV in 1362. Even the crumbling brewery walls are noteworthy: they were partly built with stones and Gothic arches recovered from the ruined castle of Rýzmberk, which had been sacked by the Swedes in 1641. Supposedly the thick brewery walls had also hidden the ancient brewing log that gave Kout its secret recipe.

When a group of writers—myself included—traveled out to Kout, I remember explaining why I had my doubts about the book, and why I tell people I’m not sure it exists today: mostly because Czech beer isn’t about recipes. A good Czech Světlý Ležák is usually pretty close to what homebrewers refer to as a SMaSH, a beer made with a single malt (100% pilsner) and a single hop (100% Žatecký poloraný červeňák, otherwise known as Saaz). It’s brewed with a double or triple decoction mash, fermented cool with a Saaz strain of Lager yeast at 7-11º Celsius (45-52° Fahrenheit), then conditioned at close to freezing for one to three months. That’s the recipe.

“The first time I went out there on vacation with my family. The second time I went to film a spot with Anthony Bourdain for No Reservations, during which I fell through a hole in the floor of the ruined old malthouse and nearly broke my leg.”

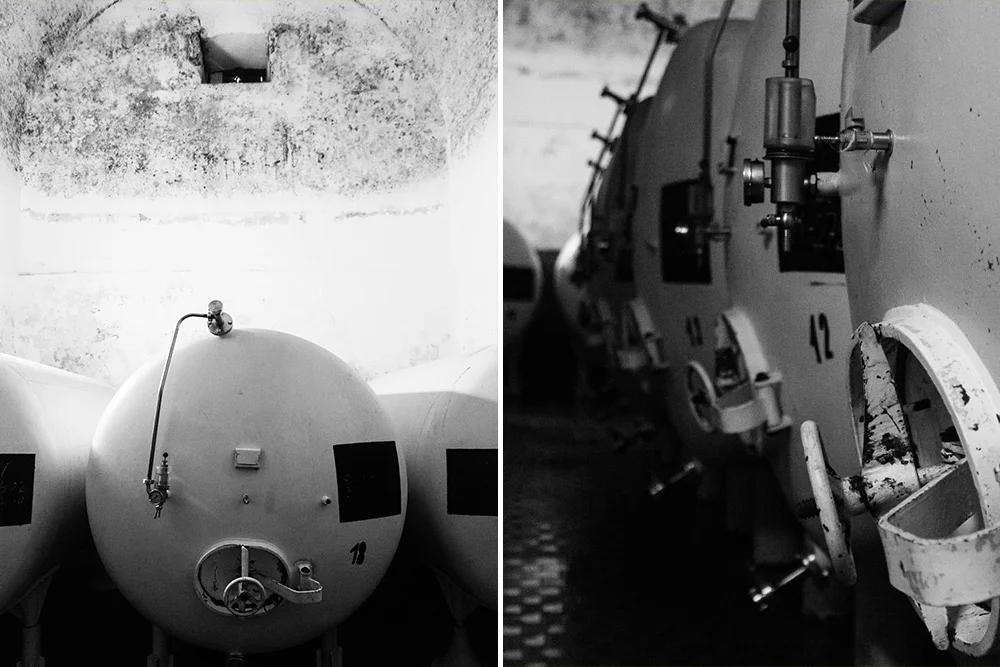

Since most people here use the same hops, malt, and yeast (Kout actually used to buy yeast from Budweiser Budvar, also known as Czechvar, and when they switched suppliers no one noticed), water is the biggest variable in terms of ingredients. And all Czech brewing water is extremely soft. Equipment has an influence on flavor, too: gas-fired kettles versus steam, open fermenters versus CCTs, as well as the fermenter geometry and the type of conditioning tanks the brewery uses. But in terms of recipes, there aren’t too many secrets.

We had our tasting in a meeting room with owner Jan Skala and brewmaster Bohuslav Hlavsa, during which they told our group a small detail they’d admitted to me on one of my earlier visits: their Pale Lager wasn’t actually a SMaSH, as it included a pinch of caramel malt. That might have seemed like a secret, but several other Czech breweries do the same, and I didn’t think anyone needed a long-lost brewing log to figure that out. We tried the brewery’s two Pale Lagers, brewed at 10º and 12º Plato, which Skala and Hlavsa served to us with comically high caps of thick foam. (Czech Lagers are definitely supposed to have a head, and good foam is considered a sign of good beer here, but I remember thinking it seemed like they were showing off a bit.)

After tasting the beers, Hlavsa showed us around the facilities. They’d cleaned up the place significantly since my previous visits, but it still looked like a wreck. In the last chapter of my essay I’d mentioned walking into a meeting where Skala and Hlavsa were discussing the possibility of a new brewhouse. That new brewhouse had already been installed, Hlavsa told us proudly.

We kept taking photographs and asking questions as we walked through the brewery. Toward the end of the tour, Hlavsa led us into a dark and frigid conditioning room, where he drew samples of Kout’s 18º Dark Lager for us, a special brew with 9% ABV. It was way too cold, of course, but the beer tasted amazing: a smooth gulp of cocoa and gingery spice with a coffee-like finish. Everyone was impressed by it, and I translated their praise to the brewmaster.

Hlavsa pointed to the marks on the conditioning tank and explained that they showed that he had brewed the beer back in January. We were visiting on the first weekend in September, which meant it had been lagering in the freezing cold for eight months. It normally got nine months or more of conditioning. It was still too young, he said.

Back outside, our eyes readjusted to the brightness. Hlavsa fed the fish in the brewery’s carp pond while we drank more beer and took more pictures. Then we got back in the van and headed towards Prague, drinking plastic bottles of Kout the whole way.

That was the last time I visited Kout na Šumavě.

The old brewery at Kout na Šumavě is still going today, which shouldn’t surprise anyone who knows anything about its history. Founded in 1736, the brewery has survived multiple revolutions and invasions, including both the Nazi and the Russian occupations, as well as its nationalization under communism. When it was reopened by Skala and Hlavsa in 2006, the brewery was coming back from an almost-40-year closure ordered by the central planners in 1969. Despite all the setbacks, Pivovar Kout na Šumave is still out there in the deep Šumava forest, still making the same four beers as on our visit. For now, anyway.

But a few things are said to have changed since the last time I went out to Kout na Šumavě. Hlavsa eventually retired and is no longer brewing. And while the beers from Kout have been good, its influence seems to have faded a bit. While there used to be about 20 pubs in Prague listed on the “where you can find our beers” section of the Kout website, distribution in the Czech capital has dried up. New craft bars like BeerGeek might seem like a natural outlet for Kout beer, but you’re not likely to find it there.

“I wanted to have Kout in our bar, but it’s hard to get,” says BeerGeek’s owner, Ruslan Shishmintsev. “Communication with the brewery is definitely not easy.”

Meanwhile, new breweries like Břevnovský Klášterní Pivovar and Únětický Pivovar have started selling extremely well-made, remarkably Saaz-inflected and rather bitter Pale Lagers, effectively stealing Kout’s shtick. Weirdly, though, some of Kout’s fellow breweries seem to act like Kout isn’t really part of the gang. Kout doesn’t appear at most of the cool beer festivals here. They don’t hang out and take selfies with other Czech brewers. They’re just these weird loners out in the Šumava forest, and while I don’t know all of the politics, there are clearly some involved. I’ve asked before, several times, but whenever I mention Kout, other Czech brewers usually just roll their eyes or say nothing at all.

Maybe because I’ve been drinking so much Břevnov and Únětice lately, the few times I tasted Kout beer over the past couple of years I thought it maybe wasn’t quite as good as it was back in the day. I’ve heard similar stories from bar owners like Libor Kult at Prague’s Kulový Blesk pub.

“When the beers first came out, they were just amazing,” Kult says. “And then for a while they weren’t as good as they used to be.”

But maybe they are once again. A couple of months ago I met a couple of old friends at one of the only pubs in Prague that still regularly serves Kout, U Kacíře in Vinohrady. It was a warm, rainy summer night, and we drank Kout’s 10º Pale Lager on the covered terrace and talked until we had solved just about all of the world’s problems. There were eight other regional Czech beers on tap that night, but after the first sip of Kout, we didn’t bother trying any of the others. It wasn’t just like how Kout beer used to taste years ago: bright and hoppy, slightly sugary and refreshingly peppery in the finish. It was more than a return to form. It was magical.

One other thing happened since the last time I went out to Kout na Šumavě: I found out where I can better research the real history of the brewery, not just the story of the brewing log and related myths. Although I haven’t been able to spend any time with it yet, this year I discovered a collection of documents from Pivovar Kout na Šumavě—pretty much all of the old papers that exist—inside the extensive brewing archives at Pilsner Urquell. Maybe somewhere in there I’ll uncover the secret of Kout na Šumavě after all. In the meantime, they get to remain out there in the woods, confounding everyone.