It may not be evident to the casual drinker, but the cider world is experiencing a bit of an identity crisis. The star among alcoholic beverages for the last few years, cider enjoyed near-triple growth rates from 2012 to 2014. This attracted large players, who rushed into the market with great ad campaigns, but products slapped together as an afterthought. New companies — both big and small — sensed something like craft brewing’s trajectory and raced into the market before they learned the art of cider making. For the first time in years, cider’s sales actually fell at the end of 2015. All this activity has left consumers confused as they navigate increasingly unreliable store shelves for tasty ciders. What the world needs now is a captain to help them chart these rough waters.

Or as one Northwest cidermaker would have it, a Reverend.

One of the most interesting American cider makers plies his trade on a leafy side-street just at the edge of bustling Portland, OR. His name is Nat West, the real person behind the doppelganger who serves, Colonel Sanders-style, as the company mascot. The two have something in common, but they get to the business of evangelizing for cider in entirely different ways. Reverend Nat, the mascot, is like an itinerant 19th-century preacher bringing a tent revival to town. (When the cidery releases especially rare ciders, they even call them “tent shows.”) The language of Reverend Nat is formal and archaic, written in cramped typeface on a label that looks like it came straight off an old printing press:

“Please savor my flagship cider. The finest fermented apple juice to ever pass your lips. My palate does not agree with unduly sweet nor simple ciders and to relish this drink to topmost effect, I sincerely wish yours to be alike.”

And: “My colleague, the distinguished cider professor Mr. T. Scrivener, concocted this unprecedented recipe for your gratification.” It’s a charming and magnetizing personality, and it's no wonder that the small company has been in a constant growth cycle since its founding in 2013.

But West, the human behind the business, holds ideas that are both more interesting and more radical than his ad-copy counterpart. He would like drinkers to reconsider the very nature of cider. America is in the first phase of a new cider renaissance in the U.S.—and the reclamation of a very old tradition. Cider making has been so long absent from the United States that there remains no tradition to rebuild. Instead, cider makers are starting from scratch. Many are looking to European traditions for inspiration, not to mention fruit. In the past half-decade, acres of new orchards have gone in, bearing the pedigree of Europe’s finest cider apple varieties. But West doesn’t think America should be looking across the Atlantic.

“American cider should have an American taste to it,” he says. “I’m not defining what an American taste is, but an American taste is not English, it is not French. If you’re trying to create a style or a culture, don’t use other existing styles as your reference point. Look at what you have on hand here, and what people here are already used to and accustomed to. No one is accustomed to drinking French and English cider — no one has any idea what English cider is.”

For his part, West looks to a tradition closer at hand. Cider has a lot in common with wine (it is, after all, a fruit wine), but this cider maker is more inspired by the scores of breweries in his home city. He’s a big beer fan, and his approach looks a lot more like a brewer’s than a vintner’s. “I introduce myself as a beer drinker who makes cider,” he says. “I drink about as much beer as I drink cider. I got into cider because I love beer.”

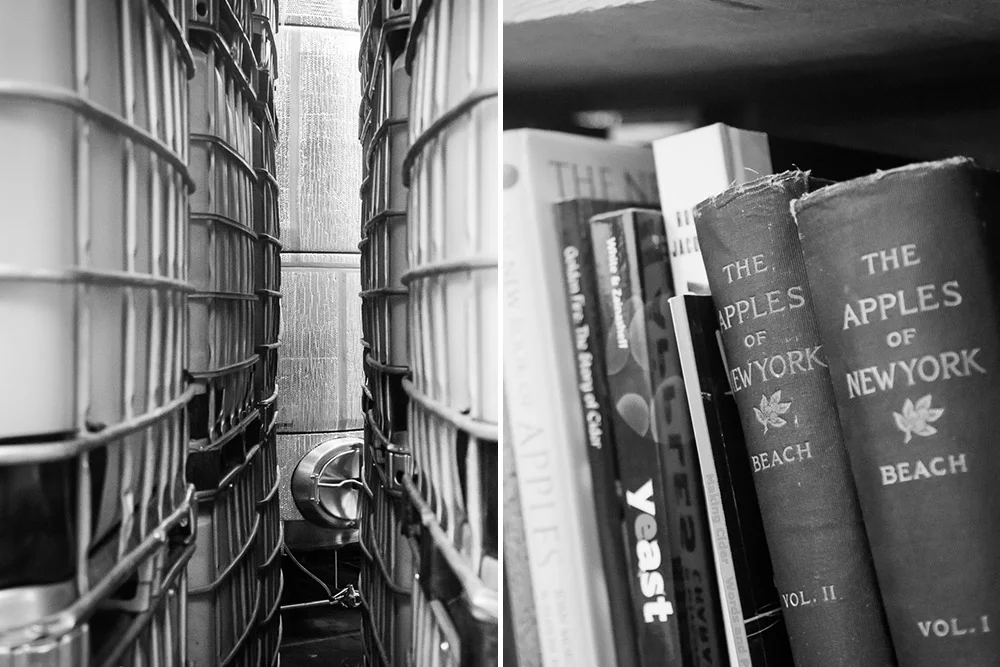

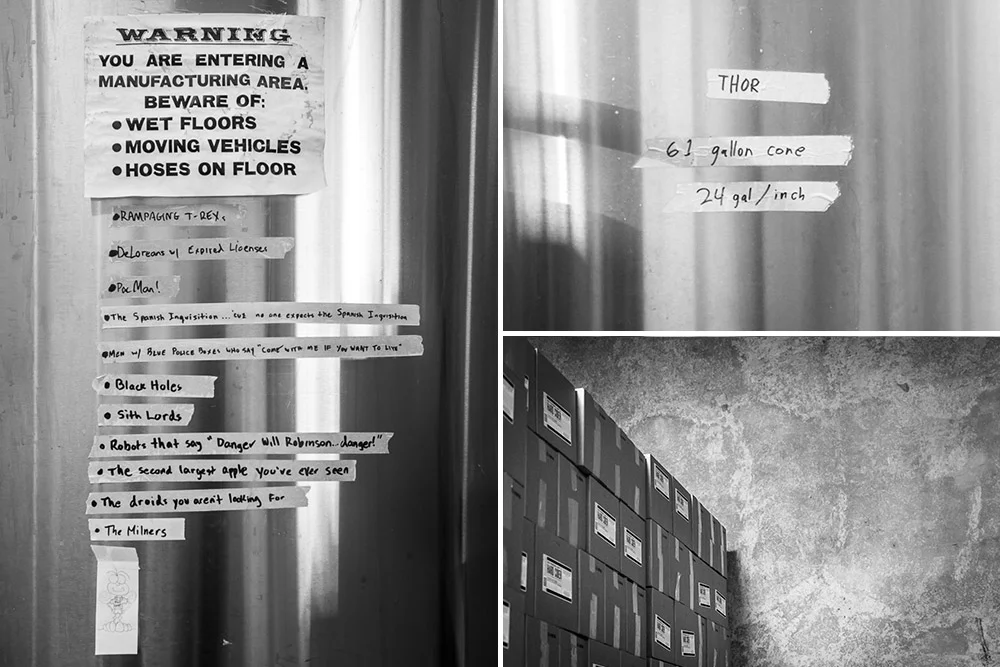

West’s cidery is an industrial space and has the look and feel of a craft brewery. There’s a lot of stainless steel, a constant thrum of movement, and the floors glisten from recent washings. What you don’t see are trees or barns or anything suggestive of the bucolic world of orchard-based cider making like you do at Rack & Cloth or EZ Orchards.

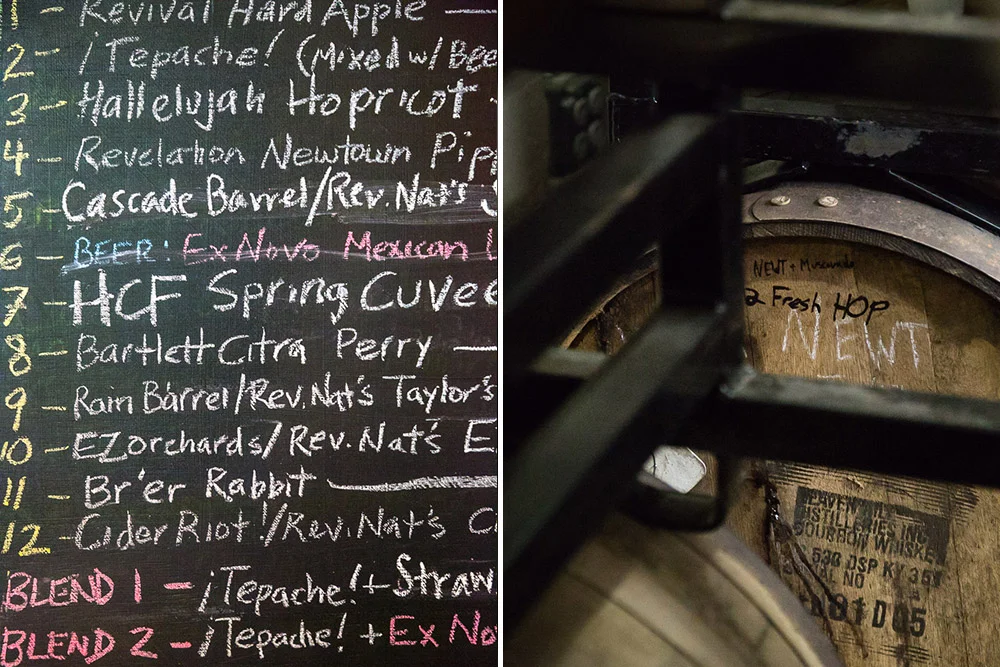

West’s is one of a growing number of urban cideries with no connection to the land. (And he has no aspiration to be an orchardist.) Reverend Nat’s does have an accordion-style press which they use on ripe fruit in the fall, but this accounts for a minority of the output. Instead, Nat mostly buys juice from orchards in Hood River and Yakima. Among the cider makers striving to make exceptional products, there is often a strong sense of the terroir of the fruit, a feeling that the cider should express the flavor of the region it came from. West, thinking like a brewer, treats the juice like an ingredient. He doesn’t strive for simplicity, but instead manipulates his cider, using different strains of yeast (many of them beer strains), other fruit juices, spices, and of course, hops. One of his most popular ciders doesn’t even use apple juice. A traditional rustic drink called ¡Tepache!, it was originally made in Mexico using pineapples. Nat uses his press on fresh pineapples and releases ¡Tepache! on Cinco De Mayo — offering it at the cidery blended 50/50 with Mexican beer, as is common south of the border.

“West thinks of ciders like brewers think of beers, recipes constructed with different ingredients, techniques, and fermentations.”

This thinking is typical of his approach. West thinks of ciders like brewers think of beers, recipes constructed with different ingredients, techniques, and fermentations. A sampling of the kinds of ciders he makes includes: The Passion, a cider made with passion fruit, vanilla, and coconut meat; Br’er Rabbit, which starts with a blend of apple and carrot juice, and then is back-sweetened with carrot honey; Hallelujah Hopricot, the cidery’s flagship that West compares to a Belgian witbier, made with coriander, orange peel, paradise seeds, apricot juice, and hops, and fermented with a saison yeast; and Providence, a version of a 17th century New England cider fortified with muscovado sugar and raisins, and spiced with cinnamon and nutmeg.

But beyond ingredients, West also uses unusual and sometimes completely novel techniques. He ferments Sacrilege Sour Cherry with Lactobacillus to create a vividly tart cherry parfait. Looking into the archives, he discovered ciderkin, an old English drink made by soaking spent apple pomace with water and creating a low-alcohol “small cider.” West ferments his ciderkin naturally without adding yeast, and the results have tasted variously like West Country English cider or Spanish sidra. But West’s most ambitious projects take him further from the realm of traditional ciders into an unexplored terrain.

Last year, he partnered with Baker City, Ore.’s Barley Brown, a brewery famous for its use of hops. For years, hopped ciders have been a northwest staple (Reverend Nat’s has even hosted a hopped cider fest), but these all effectively use the dry-hop technique of cold-extraction. West wanted to use all the properties of the hop. (“I wanted the bitterness,” he said.) What resulted was a fascinating beer-cider hybrid. Borrowing the equipment at Hopworks Urban Brewery in Portland, West boiled 500 gallons of cider for an hour and hopped it like a brewer would dose a kettle of boiling wort. (“I wanted to make a triple IPA in cider form,” he said.) The result was Envy, the first in a series based on the seven deadly sins, and it has tons of that hoppy bitterness, just like beer.

Even more importantly, it was the first of what West calls his “fire ciders.” Riffing on ice ciders, which are made by pressing frozen fruit and extracting concentrated juice, Reverend Nat’s applies heat to create the reduction. It allows the cidery to get similarly intense, jammy flavors without waiting for mother nature to provide the right circumstances (which, in Portland, simply aren’t possible).

West came to these approaches precisely because he didn’t have the kind of quality fruit many cider makers say are necessary to produce complex, sophisticated flavors. Here’s where West’s views start to look not only heterodox, but subversive. Why, he asks, should we accept that definition of “good?” He readily acknowledges that Northwest eating apples don’t produce complex flavors in cider. But, he says, “they’re so plentiful, and they’re local. You can’t argue with that. So I think that mentality of use-what-you-got defines the taste that comes out. Cascadia, the blue can, that is as Northwest as you can get. Anthem is as Northwest as you can get. There’s no other additive flavors to it, it’s all just Northwest ingredients, all Washington apples—I mean, I even use Wyeast yeast [from Oregon]. It’s all here.”

Nat West and Reverend Nat are similar in one respect: they’re both blunt and outspoken. West has criticized some cideries for using what he thinks are debased methods of making cider. Despite his own inventive methods used for getting around his geographical and industrial constraints to either make up for, or highlight, the region's compromised state of agriculture in apples, he decries the use of apple juice concentrate to make cider, which he says is always a compromise.

“In practice, this means that the cheapest possible way to make cider is to use 8% apple juice concentrate from the cheapest source (China), 8% government-subsidized and GMO high fructose corn syrup, and 84% water,” he says.

[Editor's note: This is a common refrain from West, and indeed, China is becoming a massive supplier of apples to the international market and its industrial—and sometimes craft—cider makers. Other large-scale cider makers like Angry Orchard, the subject of so much industry subtweeting, continue to happily source their apples and concentrate from traditional Western European sources (the only place on earth with the quantities they require) and skip the additives West describes. But like a true Reverend, West knows the value of a "big bad" in the storyline, and it's a storyline we've seen play out quite effectively in craft beer's early days as well. -Michael Kiser]

This conforms to the company’s language about quality and craftsmanship, but it rubs some people the wrong way—particularly because West breaks so many other rules when he makes his cider. Why is it kosher to add sugar to Providence and Envy, but wrong to add it to ciders made with juice concentrate? How can anyone who uses ghost chilies, coffee, and carrot juice make claims about purity?

But maybe consistency isn’t West’s strongest suit. Indeed, even characterizing him as an experimentalist fails to capture the full scope of his interests. Despite the exotica he’s famous for, West himself loves traditional cider. He is a huge admirer of Kevin Zielinski of EZ Orchards, who makes only traditional, naturally fermented French-style ciders, and with whom he’s collaborated. West has even made traditional English-style cider from bittersweet fruit. He champions cideries across the region and hosts the Portland International Cider Cup to help create interest in local cider, including many traditional products.

“In the end, expanding boundaries—and minds—is what animates West. ”

In the end, expanding boundaries — and minds — is what animates West. He would like people to think about all the possibilities in cider, rather than just emulating what already exists. “We can grow bittersweet apples here, we can make ciders with bittersweet apples, but do we need to?” he asks. “Who says that’s better, that that’s desirable even? You’ve got great apples here — it’s still called cider.”

Sometimes, it’s even called ¡Tepache!