In most French cities the size of Hochfelden, the trains don’t bother stopping anymore. Here in the countryside not far from the German border, weeds often cover the tracks, while stations are mostly left unattended, decaying slowly. Yet this small Alsatian town of 4,000 souls is an easy, 20-minute train trip from Strasbourg, the biggest city in northeastern France, with connections running every half hour, every day of the week. In rural France, this is quite rare.

Without this crucial rail link, the trajectory of Hochfelden’s Brasserie Meteor might not have been the same. When the Paris-Strasbourg train line was launched in 1852, it included a stop here, allowing the brewery to receive raw materials and distribute its beers quickly. By 1855, the Alsatian brewers had obtained their own train wagon for beer shipments—initially just once a week, then daily.

Even today, it’s not a long reach to say that the beer industry in Alsace—a historic region for hop growing and brewing—and the jobs it creates in the area may be what has kept the Hochfelden train connection alive. Brasserie Licorne, one of France's biggest breweries, lies just ten miles away in Saverne, the last stop on the line.

But good transportation can’t be the only reason for Brasserie Meteor’s longevity. While most of the 2,800 breweries in France closed after World War II, with only 116 remaining by 1950, Meteor stood strong. It’s still here, 384 years after it first opened, holding the title of the oldest operating brewery in France.

It’s unusual to find a big production site in a town center in France, but Meteor brews its 500,000 hectoliters (about 420,000 barrels) right in the middle of Hochfelden. The gigantic silo, with the brewery’s name in large, bright red letters, is unmissable from afar, giving Meteor a place in the skyline.

The aroma of wort that blankets the streets is also part of the town’s atmosphere, with Meteor brewing as often as seven days a week in the busy season.

Following that scent will lead you to a beautiful iron gate, which opens onto a paved courtyard enclosed by two impressive buildings, with the brewhouse at its center.

Beer has been made here since 1640, when Jean Klein founded the brewery in what was then just a farmhouse and stables. A maltings once stood in the location where the modern brewhouse was built in 1959.

As the business grew stronger over the centuries, land was acquired and new buildings and facilities were constructed around the old farm, resulting in a patchwork of architecture dating from the 17th century to the 21st, with the last constructions coming in 2015.

“When I took charge of Meteor, there were twenty-one independent, family-owned breweries in Alsace. They all closed or lost their independence, except for us. ”

Owned by the Metzger-Haag family since 1844, Meteor has always been independent. As its sole owner, the family has refused every takeover proposal. Its new CEO, Edouard Haag, is the eighth generation to lead the business, after his parents, Michel and Yolande Haag, handed over the reins in 2021.

Here in Alsace, Brasserie Meteor is seen as a point of local pride: The saying “Meteor jusqu’à la mort” (or “Meteor until death”) was invented by the beer’s fans here, not by any advertising agency. Under its new CEO, the brewery has explored a different path in recent years, expanding its audience while maintaining its flagship Meteor Pils and sticking with its longstanding tradition of independence.

So how did Brasserie Meteor manage to last for almost four centuries? Hervé Marziou, a beer sommelier and authority on the history of Alsatian beer, points to the Haag family’s disinclination to bring on outside investors.

“If it wasn’t for the family, the brewery might not exist today,” he says.

The family’s conservative leadership allowed the brewery to pass through difficult times, like when Alsace was annexed by Germany from 1871 to 1919, which brought about a sizable increase in taxes. Or during the 1980s and 1990s, two decades of declining beer sales and corporate buyouts. As CEO from 1975 to 2021, Michel Haag says that he refused every proposal he received.

“When I took charge of Meteor, there were twenty-one independent, family-owned breweries in Alsace,” he says. “They all closed or lost their independence, except for us.”

Edouard Haag admires his parents’ resilience during that time, noting that he declined a new buyout offer himself just six months ago. “Meteor lived through a period where beer was not popular,” he says. “My parents were told that their Pils was too bitter and that they needed to change it, but they never flinched.”

That commitment helped Meteor avoid the fate of most other historic Alsatian breweries. In 1996, both Adelshoffen and Fisher were bought by Heineken, which closed them in 2000 and 2009. In 2022, Heineken announced the upcoming closure of brasserie de l’Espérance, founded in 1746, which it had taken over in 1972.

In a sense, Meteor history is first and foremost the story of a family. You get that feeling when entering what once was the family home, where a giant timeline guides you through the brewery’s past. Looking at it is like looking at the Metzger-Haag family tree.

After it belonged to the Klein, Arth, and Ebel families in the 17th and 18th century, the Hochfelden brewery was bought by Martin Metzger, a 26-year-old brewer from Strasbourg, on April 1, 1844.

His sudden death twenty years later left the business to his wife, Barbe Caroline Herrmann, and their son Alfred Metzger. When Alfred’s daughter Louise Metzger married Louis Haag on October 7, 1898, a union between two Alsatian beer-making families led to the brewery we know today. Haag came to Hochfelden as the scion of Brauerei Ingwiller, founded in 1795 by Meteor CEO Edouard Haag’s fifth great-grandfather, Jean-Joseph Haag.

Called Le Grand Mariage (“The Big Wedding”), the event is recalled everywhere in the house, with pictures of the bride and groom, the framed original marriage certificate, and even the menu from the reception. The lucky guests were served lobster, truffled turkey, and deer saddle, with both wine and champagne pairings, but no beer.

Louis Haag, the current CEO’s great-grandfather, is probably the most important figure in the history of Brasserie Meteor. In the old family house, his office has been kept intact for the public to visit since 2016, with the opening of Villa Meteor, a touristic experience inside the oldest buildings of the brewery.

In the office, everything is cleverly designed to make you feel like Louis Haag just left the room, with a telephone ringing left unanswered, documents on the desk waiting to be signed, and Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1 playing in the background.

The loud creaking of the hardwood floors adds to the atmosphere, as you can imagine Haag pacing up and down his office or standing in front of the huge window overlooking the garden, from where it’s said he used to share important news to Meteor’s employees.

Louis Haag made two decisions that shaped the brewery into what it is today. The first was choosing the name Meteor in 1925. Family-name businesses were going out of style in the 20th century, and breweries needed catchier names. “Meteor” was chosen to convey a sense of modernity, while being comprehensible in French, German, and other languages.

With this new name came an iconic, now ubiquitous logo of a golden meteor—in Hochfelden, it’s not unusual to meet someone wearing a Meteor cap or shirt, or spot a branded umbrella in a backyard. Eventually considered outdated, the meteor logo was replaced by a capital M in 1988 before being brought back in 2015.

The name connects to the Haag family’s love for astronomy. Today, the brewery helps finance FRIPON (Fireball Recovery and InterPlanetary Observation Network), a project whose goal is to trace the origin of extraterrestrial material falling on Earth, even housing a camera from the program on the brewhouse roof.

Today, the old-school logo has also found its way back to just about every restaurant door in Hochfelden and the surrounding area.

“Unlike other people in France, Alsatians have always liked bitterness. With our history with Germany, we’re more into beers from Eastern Europe. We’ve been conditioned to it.”

At Restaurant Au Bœuf in Schwindratzheim, the most popular choice is choucroute, a traditional Alsatian recipe of sauerkraut, sausages, and smoked ham. Naturally, the owner recommends pairing it with a pint of Meteor Pils.

“Meteor is our local pride; it brings many jobs for people here,” he says.

Meteor Pils represents 40% of the brewery’s production. The pride of Brasserie Meteor, it counts as Louis Haag’s second great contribution to the company.

Meteor Pils is usually the first choice at the brewery’s taproom, located inside the former coal storage room, where guests are greeted by quite a character: Mickäel Le Bardinier.

Since the opening of Villa Meteor eight years ago, he’s welcomed visitors to the taproom, after working for seven years on a conditioning line. Once you join Meteor, he says, you never leave.

Le Bardinier isn’t his real last name, but rather a self-proclaimed job title, since he’s both the brewery’s barman and its jardinier, or gardener.

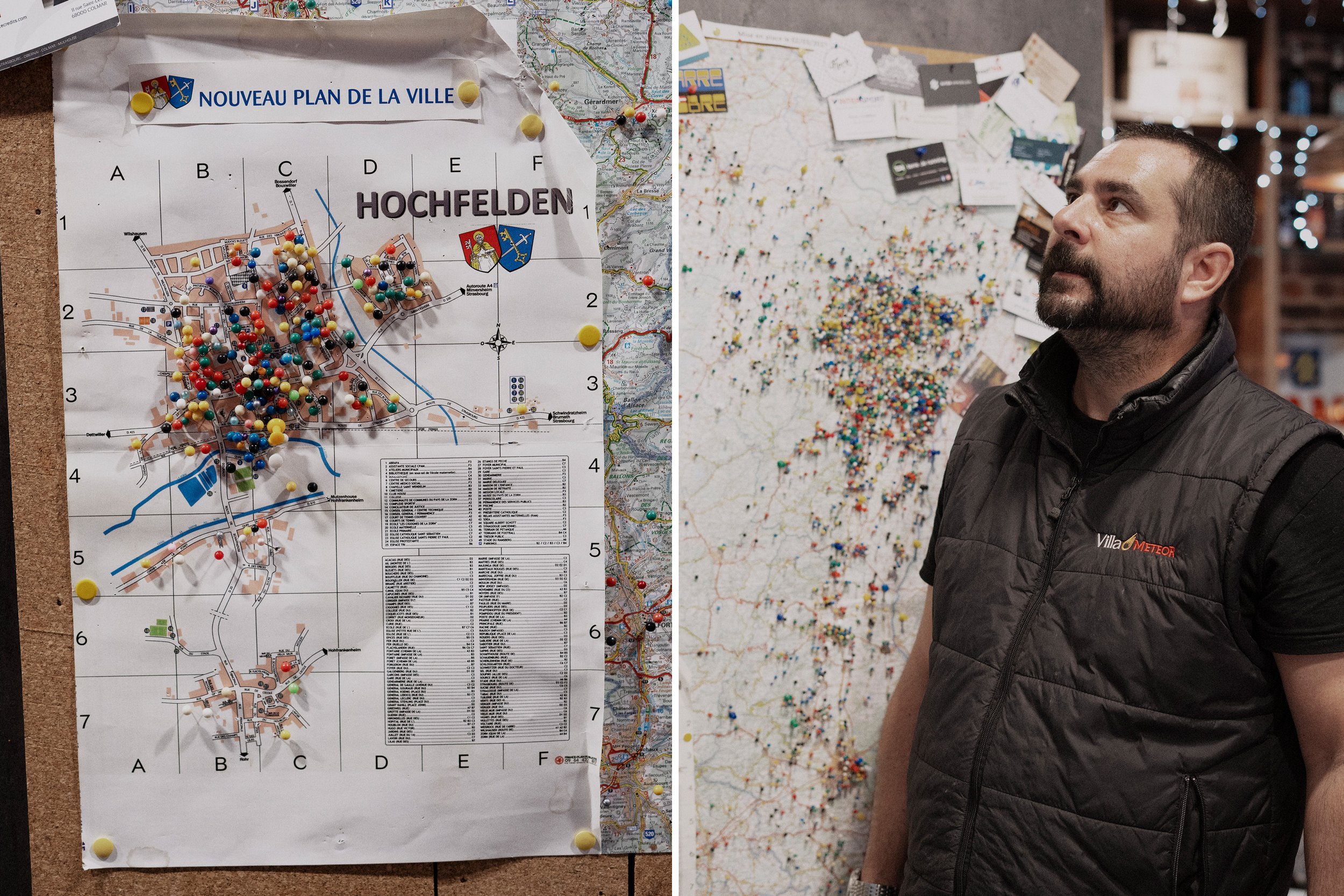

Before pouring a beer, Mickaël first asks guests where they come from and hands over a small pin. On the far wall, visitors can stick the pin into a map of the world or even a detailed map of Hochfelden, where real locals can mark the very street they live on.

The maps are given a fresh start annually, since 20,000 tourists put pins in them every year. (Soon, Edouard Haag says, visitors will also be able to stay the night in a small hotel located in the old family house, which has been uninhabited since the death of his grandmother in 2005.)

Although there are nine beers on tap, including a Märzen, a Witbier, and an IPA, Mickäel says that Meteor Pils is without a doubt the one he serves the most.

“Unlike other people in France, Alsatians have always liked bitterness,” he says. “With our history with Germany, we’re more into beers from Eastern Europe. We’ve been conditioned to it.”

He insists that Meteor Pils and all of the other beers must be served with a nice head of foam, another local touch. Outside of Alsace, many French people dislike too much foam on their beer.

After training in Berlin, Louis Haag spent a year working in a brewery in Czechoslovakia. When he created and launched his Pils in 1927, he had a Czech Pale Lager in mind, but with the beloved Alsatian variety Strisselspalt as the main hop. Michel Haag says that the Czech government gave Meteor the right to call their beer “MeteorPils” in 1931, provided that the name was followed by the phrase “Bière d’Alsace.”

Alsatian pride is a powerful force: Marziou even argues that Meteor Pils should have its own Protected Geographical Indication, or PGI.

Morgane Bontems quickly learned the importance of Meteor Pils when she joined the brewery’s research and development department in 2020. “If there’s one rule, it’s that you don’t touch Meteor Pils,” she says. “You can improve the process, but you stay away from the recipe.”

As Meteor’s head brewer since 2020, Anne Perra-Lorioux says she’s brewed the recipe she was given when she arrived, without ever making any alteration. “It’s important to respect this tradition, even more when there’s no need to change a recipe that’s already working as it is.” The only real modification was made in 2010, with the addition of a small portion of Aramis, an Alsatian hop that is significantly more bitter than Strisselspalt.

“We use Meteor Pils as a reference to show the finesse of our Alsatian hops to our international clients.”

That cultivar was developed by the hop producer and supplier Hop France, whose headquarters are located in Hochfelden. Antoine Wuchner, a sales manager at Hop France, says that he often brings business guests to Villa Meteor.

“We use Meteor Pils as a reference to show the finesse of our Alsatian hops to our international clients,” he says. “Although we export 70% of our production, we’re proud to work with Alsatian breweries like Meteor, our client with the lowest shipping cost.”

With Alsace representing 55% of Meteor’s sales and most of the remainder going elsewhere in France, international exports amount to just 5% of production, primarily heading to the U.K., Italy, Norway, Sweden, South Korea, Germany, and the United States. Meteor Pils makes up the bulk of those sales, often thanks to expatriates, according to Frédérique Billard, the brewery’s export manager.

“When an Alsatian opens a business abroad, they often call us, because they want to serve what they know best, Meteor Pils,” she says. “The pandemic slowed down our progression but we’re now opening up to new states, like Florida.”

Inside or outside Meteor, everyone I talked to called Edouard Haag’s 2014 arrival a game changer. With a background in business management, he began work as Meteor’s sales manager, before taking on the managing director role in 2018.

The return of the golden meteor logo in 2015, the opening of Villa Meteor in 2016 and the 2019 launch of the 17,200-square-foot Le Meteor, the biggest restaurant in Strasbourg, are all projects initiated by Edouard Haag, though he speaks of them as team efforts.

“The brewery has entered a very creative phase with him,” his father says. “There were always three conditions to one of my kids taking over the company. They must want to do it, they need to have the skills to do it, and it must not be a poisoned gift or a burden.” In other words, the brewery had to be in good shape before it could be passed on.

“I was 33 years old when I became Meteor’s brewmaster, replacing Jean-Marie Kessler, who had held that position for 33 years. On my first day, Michel Haag told me he’d only met five brewmasters during his entire career.”

When I talk to Edouard Haag, he recalls the exact same thing, practically word for word. “In the family we do not consider ourselves as heirs: We pass on,” he says. “An heir benefits from their inheritance, and that’s it. I work for the next generations, and I don’t just mean my children, but also the others who work for this company. We invest for the long term.”

The long term never felt so literal for Perra-Lorioux as when she joined the team.

“I was 33 years old when I became Meteor’s brewmaster, replacing Jean-Marie Kessler, who had held that position for 33 years,” she says. “On my first day, Michel Haag told me he’d only met five brewmasters during his entire career. You have to be up to it.”

The longevity of Meteor staff has also led to funny situations for its new CEO, whose childhood in the brewery is recalled in the villa, where a picture shows him, just a few months old, dressed in Alsatian attire, with a nursing bottle of beer.

“We have people retiring who started working for the company before I was even born. Some knew me as a kid wandering around the facility. This was my playground,” he says. He played hide-and-seek here with his siblings and scared himself while exploring the deepest cellars. “Knowing each other for so long creates a lot of mutual respect.”

Edouard Haag believes that every generation has left its mark on Meteor: Louis Haag’s defining decisions, Frédéric Haag’s robust quality control, and his parents’ strength during difficult times.

When it comes to his own legacy, he says that only the future will tell.

“I come with the issues and desires of my generation, like sustainability, which we cannot ignore,” he says.

To reduce its energy consumption, Meteor plans to install solar panels, which will cover 10% of its electricity needs. The brewery also now invests 10% of its annual turnover into upgrading equipment—a blessing for the production team, which has to deal with a special kind of heritage: old machinery.

“Lots of our equipment has been salvaged left and right, bought from closing breweries 50 years ago, like the grist mill, which got here before I was even born,” Perra-Lorioux says. “We invest to diversify our range and work with new raw materials. Replacing the grist mill will mean being able to work with harder grains, like rye, which we’re not able to do at the moment.”

Replacing the 65-year-old brewhouse is also in discussion, since Meteor has almost reached its production capacity. Though the brewery could most easily build a new production site elsewhere, that idea has always been out of the question, according to Marziou.

“Michel and Yolande wondered if they should leave Hochfelden to build a more modern unit, but leaving the village would mean losing a part of what makes Meteor,” he says.

Edouard Haag agrees.

“Between improving our financial results a little bit or keeping what makes the soul of Meteor, our choice has been made,” he says. “If we leave Hochfelden, Meteor would just be an image, and a poorly marketed one.”

Discovering the U.S. craft beer scene has been an inspiration, he says.

“Up until six years ago, we didn’t know how to dry hop or brew with fruits. For a long time, our only top-fermented beer was a Hefeweizen,” he says. “We were seen as a bit dusty, which wasn’t entirely wrong. We are lucky to have always benefited from a good image here in Alsace, but that wasn’t always true outside our home region.”

“If we leave Hochfelden, Meteor would just be an image, and a poorly marketed one.”

Since Meteor produces more than the limit of 200,000 hectoliters (roughly 170,400 barrels), it doesn’t fit the legal definition of a “small, independent brewery” that defines good beer for many French people. But in the future, the brewery hopes to leave behind the assumption that “large” equals “uninteresting.” Recently, that has meant diversifying, with several additions to its core range, and a new line of one-off beers.

For its IPA, the brewery partnered with Hop France to help develop an experimental cross between Strisselspalt and Cascade that was baptized with the anagram Teorem. The brewery’s new investments, recipes, emphasis on sustainability, and experiments are helping to change Meteor’s image among craft beer fans.

For Perra-Lorioux, Meteor truly is an artisanal brewery, especially compared to some of the larger producers where she worked previously. But when she talks about it, she uses an English term while speaking French.

“Everything I do is ‘craft’ — I have control over the whole process. I can experiment and do whatever I want,” she says. “Meteor’s business plan is to keep the brewery healthy for the next four generations. It’s not short-term profit. That’s a very different state of mind.”