Hospitality is rare and precious in the wilderness. Being welcomed to share anything, even just a log on which to sip a mug of weak instant coffee, blazes with profound magnanimity. When your surroundings are indifferent at best and unwelcoming at worst, an outstretched hand is a jolt of human tenderness. The offer of shelter, that most primary of needs, can connect people across cultures and language barriers.

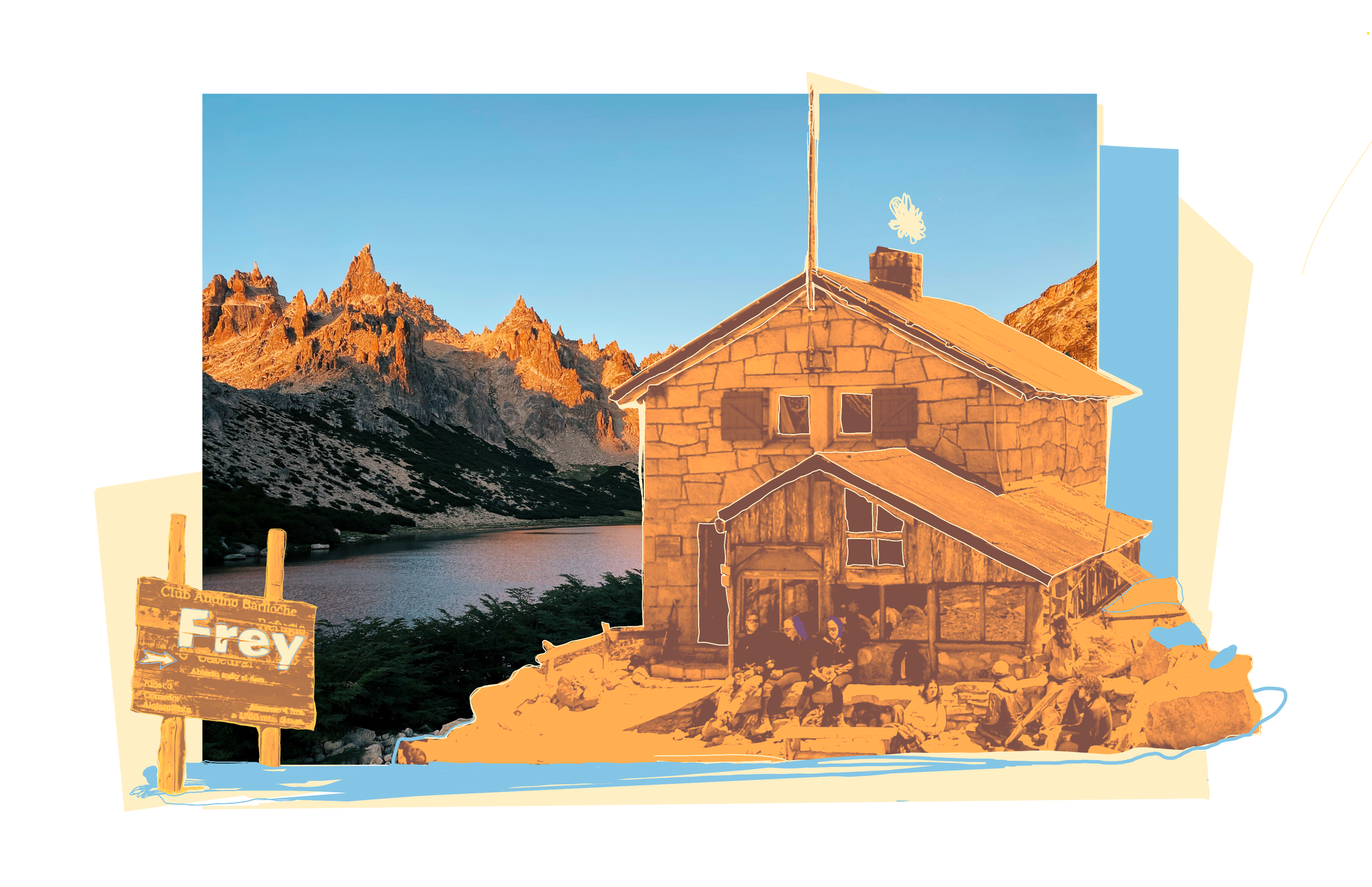

I didn’t have lofty expectations of the hospitality I’d receive at Refugio Frey. Logistically, I knew the basics: The refugio is essentially a small, cinder block cabin on the edge of Laguna Toncek in Nahuel Huapi National Park, outside San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina. Built in 1957, it’s inaccessible by road; the only way up is by foot, a 6.3-mile, 2,350-foot ascent from the Villa Catedral trailhead. It’s owned by the Club Andino Bariloche, an organization based in the Andes, and has for 66 years provided basic services—shelter, namely, but also food and toilets—to mountaineers, climbers, backpackers, and day hikers. It takes the latter portion of its name from Emilio Frey, an Argentine geographer and the first superintendent of Parque Nacional Nahuel Huapi.

It was the first half of its name, though, that gave me pause. The word refugio was coined when South American alpinists began creating their own versions of the European ‘refuge’ system: chains of modest shelters—basically huts—that provide safe harbors for climbers in rough, wintery conditions. Whether “refugio” or “refuge,” it’s a term charged with spiritual resonance and inherently defined by a contrast to whatever is outside of it. You only need a refuge if there’s something from which you’re hiding.

I turned this thought over like a pebble in my pocket as I began my hike to Frey in the early dawn light of February 2023. I had arrived at the Villa Catedral trailhead with my 55-liter pack carrying about 30 pounds of gear. This was after an hour-long bus ride from the downtown plaza in Bariloche, meaning I’d had to leave my hostel by 6 a.m. to ensure I got a seat on the first bus. By the time I arrived at the trailhead, I felt like I’d already made it through a logistical gauntlet. I’d woken up before dawn, made coffee in the hostel, packed my final belongings, performed a few stretches in my room, and navigated a foreign country’s bus system. Now I just had to climb the mountain.

“My hiking boots were well broken in, my gear organized and dependable. But mentally and emotionally, the days were unpredictable.”

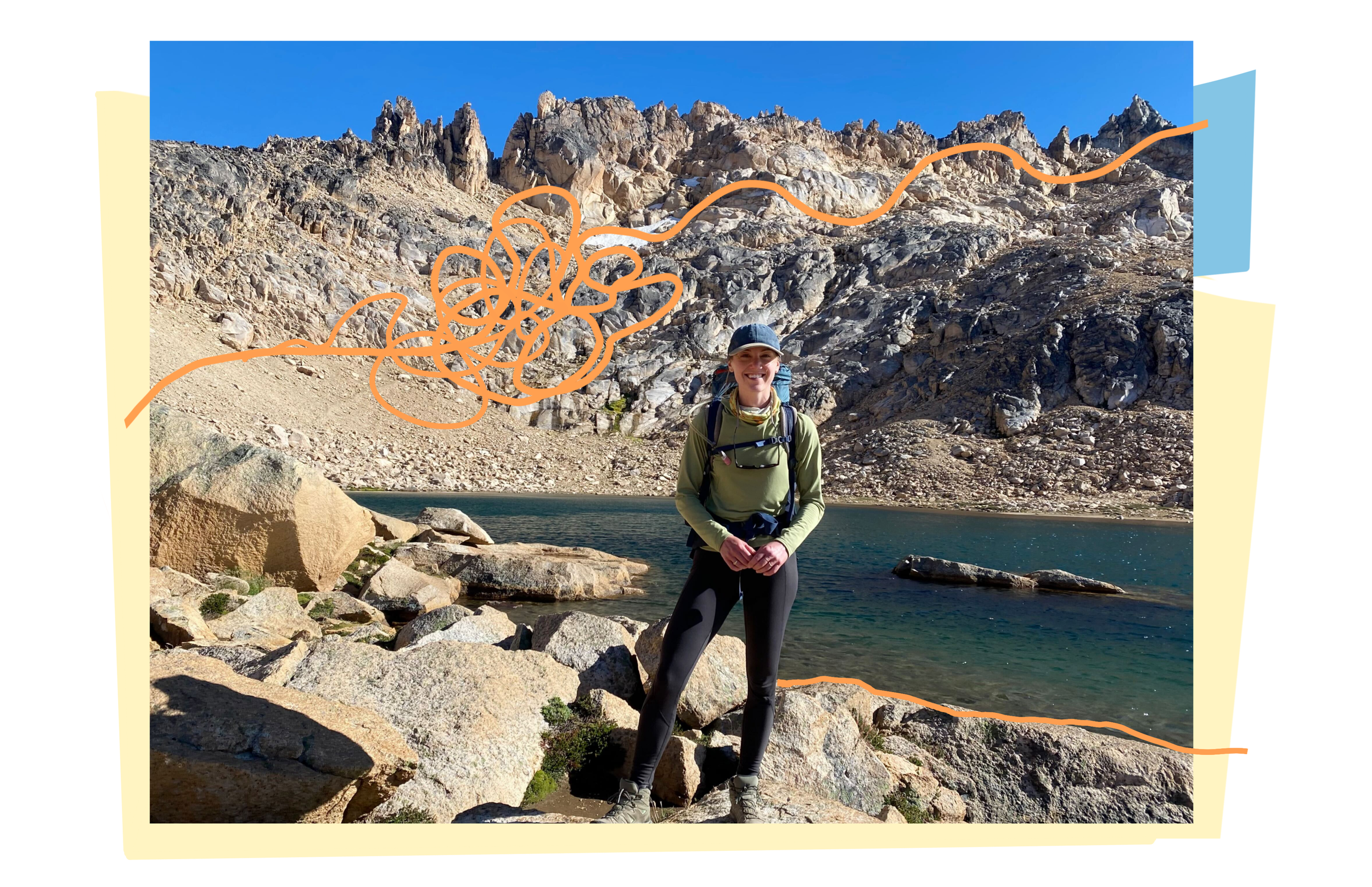

I was alone, backpacking during a portion of an extended South American vacation. More than three weeks into a month-long trip, I felt as physically strong as I ever had, having spent the previous two weeks hiking around Chile’s Atacama Desert (spending a few days above 15,000 feet) and the Chubut Province of Argentina. My hiking boots were well broken in, my gear organized and dependable. But mentally and emotionally, the days were unpredictable. Stripped of my normal life’s noise—Slack notifications, podcasts, phone calls with friends, my dog’s needy barking—I had weeks to think and to feel and to experience. This could bring elation as easily as it could bring confusion and anxiety, depending on my surroundings and the instincts they provoked.

A friend had months prior suggested I spend a few nights in the refugios in Nahuel Huapi. Stringing together stays at four of the most popular stops creates a multi-night hut-to-hut circuit, but not liking the prospect of the steep mountain pass between two refugios in particular, I opted for just a couple nights at Frey, from which I could do spur hikes to other destinations. I’d hike into Frey via the Villa Catedral trail, and come out two days later in roughly the same direction via the Lago Gutierrez route.

Frey’s website, where I made my reservations 72 hours in advance, explains the accommodations: a free spot in the tent campsites outside, or one of 35 barracks-style bunk beds inside. Meals could be purchased for an additional fee. My bunk, without meals, cost 7,000 Argentine pesos, or roughly $31 U.S. (less, if you’re able to find a favorable exchange rate during Argentina’s recent inflation crisis). Given the remote location, a worn mattress was all I expected. In the end, that’s about what I got. But while the meals were basic and the accommodations far from luxurious, the refugio still delivered a small miracle: true hospitality in the midst of true wilderness.

Providing shelter for 35 people per night and meals for as many as 300 per day without road access is a gargantuan task. Nearly all food and supplies—from onions to pork shoulders to cooking gas—are packed by staff or volunteers on foot. Trash is packed out the same way. Horses and helicopters are not allowed in the national park, but once or twice a year, the refugio is granted special dispensation to land a chopper loaded with 13,200 pounds of bulky items such as lumber and bags of flour—if a helicopter is available. The nearest one flies from San Martin de los Andes, more than 125 miles away, and is also used to fight wildfires. Resupplying beer to thirsty tourists is a low priority.

But for Guillermo “Colo” Lynch, the concessionaire who has operated Emilio Frey since last year with his business partner Juan José Puliafito, such logistics are a personal mission. Lynch’s father was a rock climber who operated the Refugio Laguna Negra—a few valleys nothwest of Frey—in the 1970s. Refugios were different then. Refugio Laguna Negra was only staffed in the high summer months of January and February. The rest of the year, a visitor was expected to bring their own food and supplies. His father could check the refugio during the off season, sometimes not encountering a visitor for weeks.

“People were satisfied with a roof,” Lynch says of that time. “Now they need service and dessert.”

“People were satisfied with a roof. Now they need service and dessert.”

Lynch took over Frey at an especially fraught time. In 2022, a young employee of Refugio Frey named Manuel Benítez died of hypothermia as he attempted to reach the refugio in a snowstorm. Lynch was among the search and rescue party that assembled to find him. He’s reluctant to talk about it, not only because it’s emotionally difficult but because there is an ongoing investigation into the prior concessionaire’s alleged role in not following safety protocols and employment laws. Simultaneously, Club Andino Bariloche was receiving complaints about accommodations at the refugio, from the quality of food to the dismal mattresses.

Lynch bid for the concession in order to turn this reputation around, arranging a private agreement with Club Andino Bariloche.

“We are trying our best to modify some things that have been not as we wanted,” he says. “The buildings are very old builds and badly maintained. We had to improve all that. We want to improve the conditions of the employees working there so we can offer better service.”

The changing composition of the visitors to Frey demands this higher level of service. In his father’s days, refugio guests were mostly hardcore mountaineering enthusiasts. They came to climb, and not much else. Until recently, the staff at the refugios was equally made up of people whose primary focus was alpine sport, not catering to guests. Visitors with a more casual interest in the mountains felt they were ignored or looked down upon by these hosts. Lynch is consciously working with his employees and volunteers to reverse this.

“Many years ago, the complaint was how bad the attention of the staff was. They used to be people who just wanted to rock climb. They were not welcoming there,” Lynch says. “We are trying to reverse this condition and say, everybody is welcome here.”

His effort seems genuine. When we spoke by phone in April, he asked me earnestly about my experience in the refugio months prior, inquiring about the names of the staff working there during my visit. In the high season, Refugio Frey employs up to a dozen people to clean, cook, log visitors, and transport supplies to make simple but fresh meals such as pizza, empanadas, and braised pork with potatoes. Lynch also maintains a WhatsApp group of about 50 volunteers who gain mountaineering experience by offering to transport supplies to and from Frey. A sign I saw during my visit also informs Frey guests that they can earn a small discount on their stay by offering to haul kitchen trash back to town.

One glass of wine and one savory empanada at a time, Lynch wants to restore Frey’s reputation. But this means offering a higher level of hospitality than in decades past, without some of the advantages of that time. (Horses were allowed in the park until 10 years ago, and visitor numbers were much lower.) Lynch feels a duty to provide for guests, some of whom are inexperienced and may be underequipped. Perhaps his job would be easier if there were fewer casual visitors drawn to Frey by the promise of wondrous social media photos. But he accepts that this is the reality, and that he has an obligation to keep these visitors safe, too.

“The times of my father, they have changed because of Instagram and Facebook.”

“The times of my father, they have changed because of Instagram and Facebook,” Lynch says. “In summertime, January and February here, [people] go with shorts and T-shirts and don't know the hardness of the season.”

I wasn’t worried about my gear during my three-day stay at Frey. My backpack was heavy with layers of clothes, JetBoil stove, food, water filter, first aid kit, and a Garmin InReach satellite communicator in case things really went sideways.

I was more cognizant of challenges of a mental or emotional sort. I got them on my second day at Frey, on a loop hike I took in the afternoon. An hour after leaving the refugio, I had lost the faint trail several times, my path a tangled orange squiggle on my GPS map as I backtracked, then tried a different spur, then revised my route again. A pair of crested caracara birds I’d passed several times seemed to regard me with increasingly quizzical avian expressions from their place on the forest floor: “Her again?” My looping footprints in the soft soil spelled out confusion.

“I was never abjectly lost—if I couldn’t find my way forward, I would double back to the rocky pass I’d dropped over a few miles prior—but wayfinding is wearying work.”

I was never abjectly lost—if I couldn’t find my way forward, I would double back to the rocky pass I’d dropped over a few miles prior—but wayfinding is wearying work. It’s depleting to problem solve when you’re alone, in unfamiliar terrain, balancing the imperative to stay calm with the need to constantly reevaluate risk. The literal low point of that hike found me extricating myself from a deep, muddy puddle that had sucked in my left leg up to my mid-thigh, coated both calves, and fully filled my hiking boots with foul-smelling muck. Without further navigational issues, I had two miles and 1,600 feet of elevation ahead of me. Mercifully, the trail grew clearer after I climbed out of the portion that ran along the boggy creekside.

A mile from my destination, when I spotted a pair of older male hikers ahead of me—the first people I’d seen in hours—the relief was palpable. Eventually, I stumbled back into base camp, covered from the hips down in mud and grinning with exhaustion and gratitude. A Canadian backpacker named Mike, who I’d met at my hostel a few days prior, appraised my bedraggled appearance. I rushed to change out of my pants and socks and rinse them in Laguna Toncek, hoping to avoid stares from the dozens of other hikers, backpackers, and climbers scattered around camp.

In dry clothes and a pair of Tevas, I melted onto a picnic bench to debrief with Mike about our day hikes. We mutually decided that a bottle of wine was necessary. The beers at the refugio cost 500 Argentinian pesos ($2.25), so a bottle of wine, at about six times that price, was a relative splurge. We ordered the better and slightly pricier of the two red wine options, which arrived swiftly at our picnic table in the hands of one of the refugio’s smiling, hippie-ish staff.

Over a free plate of shoestring potato chips, we clinked our aluminum cups together. The physical and mental whiplash seemed unreal to me: Here I sat, the sun warming my face and the red wine blanketing my stomach, laughing and commiserating with a fellow traveler who had a challenging mountain pass ahead of him the next day. Just hours ago, I had been stuck in mud, vaguely lost, struggling against my own worst mental instincts. I had found refuge.

A bottle of wine, shoestring fries, a dingy, worn, plastic mattress. They’d be considered bare bones accommodations anywhere else, but at Frey, they were communion. A safe, covered place to rest my head and a bottle of wine with which to swap adventure stories were more nourishing and luxurious to me than any steak or Champagne had ever been. The warmth I received back at the refugio felt like a hero’s welcome.

Lynch tells me that food and drink sales aren’t just critical to the mission of providing hospitality at Frey, they’re literally helping keep the refugio alive. Lodging alone could barely sustain the operation, margins on food are better, and profit from alcohol is best. Whether feeding someone’s body or offering a relaxing drink, these transactions go toward infrastructure upgrades that will improve his accommodations further. A new gas oven was installed in February with assistance from a military mountaineering unit; Lynch hopes to have new beds installed in May.

I sense tension in Lynch’s desire to improve the refugio’s hospitality. Like most publicans or hoteliers, he wants to meet or exceed guests’ expectations. But he seems a bit wistful for the era in which his father operated, when those expectations were simpler and could be satisfied by just a roof overhead or a humble stew for dinner.

“I would not say that I am proud now,” Lynch says of the facilities. “I am proud that I get to be one of the guys who is running the hut. Hopefully I can complete my dreams and improve all the stuff that I want to improve. But that really depends on time and luck.”

Manuel Benítez’s name ripples through my mind as he says this. Not every day is a fight for survival at Frey, but certain days are. The staff and volunteers of the refugio sometimes take on great risk and discomfort to provide for guests. Most of those guests are Argentinian hikers, but several people I met at Frey hailed from the U.S., Canada, Scandinavia, Europe, and Australia—many clad in hundreds of dollars of Arc'teryx and carrying thousand-dollar cameras.

Argentina was then, and is now, in the midst of an economic crisis that’s created near 100% inflation. It’s a boon to those carrying U.S. dollars in particular, but it’s devastating for lower-income Argentinians and business owners. That Lynch and his staff literally scale mountains to provide graceful service to tourists seems all the more miraculous in that context. While acknowledging how dire the country’s economic plight is, Lynch remains committed to the lofty goals he has for Frey.

The morning of my final day at Frey dawned wet and cold. From my spot in the bunkhouse, I heard sheets of rain lashing the windows and could barely make out the shapes of other sleeping guests in the thin, gray light. I rolled over, hoping the storm would blow over in an hour. It didn’t.

The promise of warm coffee eventually convinced me to squirm out of my warm sleeping bag and start boiling water outside. People who had camped in tents overnight shook water from their rain flys and rushed to the toilets with jackets held over their heads. I silently congratulated myself for remembering to pull the waterproof cover over my backpack the night before as I watched other hikers frown at their soaked bags. (Frey doesn’t allow backpacks inside, due to limited space.)

Caffeinated, I prepared to leave Frey and exit via the Lago Gutierrez trail, where I’d catch a bus and return to Bariloche. I lingered on the edge of Laguna Toncek, taking in the granite spires that rise above the lake like the remnants of a crumbled Gothic cathedral. Just the day prior I had scrambled among them; that morning, they were shrouded in low clouds and no doubt slick with precipitation.

I thought of Mike and the plans he had that day to climb over the even more challenging “cancha de futbol”—a narrow, exposed pass through the mountains above Laguna Schmoll—on his way to his next stay, at Refugio Jakob. Below the pass, a notoriously difficult scree field descends steeply to the Ruco Valley; a friend of mine who had hiked this route years prior described the descent as a “controlled slide” rather than a downhill hike. I worried about Mike navigating the wet rocks and potentially high winds, and I tried to telepathically send some positive energy his way. I saw a few days later, via Instagram, that he’d made it.

Conditions change quickly in the mountains, physically and emotionally. I had come to Frey unsure of the welcome I’d receive, or how menacing the surrounding wilderness would be. I found both to be inviting, even when they weren’t always completely comfortable. Especially when they weren’t.