The pandemic became real for me when my “one big thing” was canceled, and I suspect I’m not the only one. Mine was a mid-March trip to Vancouver—my first international non-wedding-related photoshoot—and I was so excited for the career milestone. I’d already found a running route and a camera shop near my hotel (which, at the time, I begrudged for not having a pool).

Now it’s hard to remember what that felt like, even though it was just a few months ago. Air travel seems like a thing of our germy past, camera shops are closed, and who wants to share pool water with strangers? In the meantime, the internet has quickly filled with ambitious ideas for all of this new free time. Sourdough, art, chickens; none of it felt like the type of reaction I was having to this personal and global crisis. The only solution I could find was to grab a camera, and a mask, and head out—safely—to the essential businesses of my area.

As the pandemic wore on, I began working on a documentary photography project about small Bay Area businesses and the effects of COVID-19 on their livelihoods. Most of my coverage began in Oakland, where much of my professional network is, but as the project grew, I wanted to turn my attention closer to home—to a community that doesn’t always get time in the spotlight.

I live less than 15 minutes north of Berkeley in an unincorporated town called El Sobrante. The name literally means “the leftovers,” or “excess,” though it definitely doesn’t feel that way. We know our neighbors, live within blocks of our accountant and our plumber and our mechanic, and are surrounded by rolling hills.

The town’s map snakes in and out of nearby Richmond, San Pablo, and Pinole, in the space left over from historic land grants in the surrounding areas. Livestock is allowed in El Sobrante, but not in our incorporated, neighboring towns, which sometimes leads to an anachronistic horse and rider ambling down the main drag. Attempts were made at industry, including a railroad and a dairy farm, but nothing stuck as our claim to fame until the construction of a dam and reservoir in the 1930s. San Pablo Dam Road is now the town’s main drag, and, with a few exceptions, it is lined with independent, owner-operated small businesses.

Gentrification has changed the Bay Area dramatically over the last couple decades. It's encroaching here, too, though many of the outward signifiers are only just appearing. A modern-looking dispensary recently opened up, and it stands out awkwardly every time I pass by. Many people in the Bay Area still don’t know where we are. A number of the town’s small shops are run by immigrants, and they have worked without a break during the pandemic—protected only by newly installed Plexiglass screens and face masks.

“I look forward to the time when neighbors aren’t potential disease vectors, when supporting a local business doesn’t feel like putting anyone at risk.”

I speak English and Spanish, but those two languages aren’t always useful at the small shops in my town. In building this project, I’m aware of the need to approach possible subjects with care and respect, and of the new challenges inherent to this moment. Asking for an unsolicited portrait by waving around my large camera isn’t exactly inviting—particularly when keeping my distance from subjects, and especially with a face mask on. There is a lot of camaraderie and comfort that is lost behind a mask.

My neighborhood tour coincides with the errands I need to run, and I begin at Oliver’s Hardware, where I often go for essentials. Oliver’s has been around since 1943, and is one of those shops that looks like it can’t possibly have every little thing you need, but knowing employees somehow always find whatever you’re looking for. Lucky me—they even have hand sanitizer!

The always-smiling Alice greets me, and is more than happy to pose for photos. As we chat, I learn that the store has been on the news a few times, most recently for making mask donations during the Paradise fires. Here, a camera during times of crisis is nothing new.

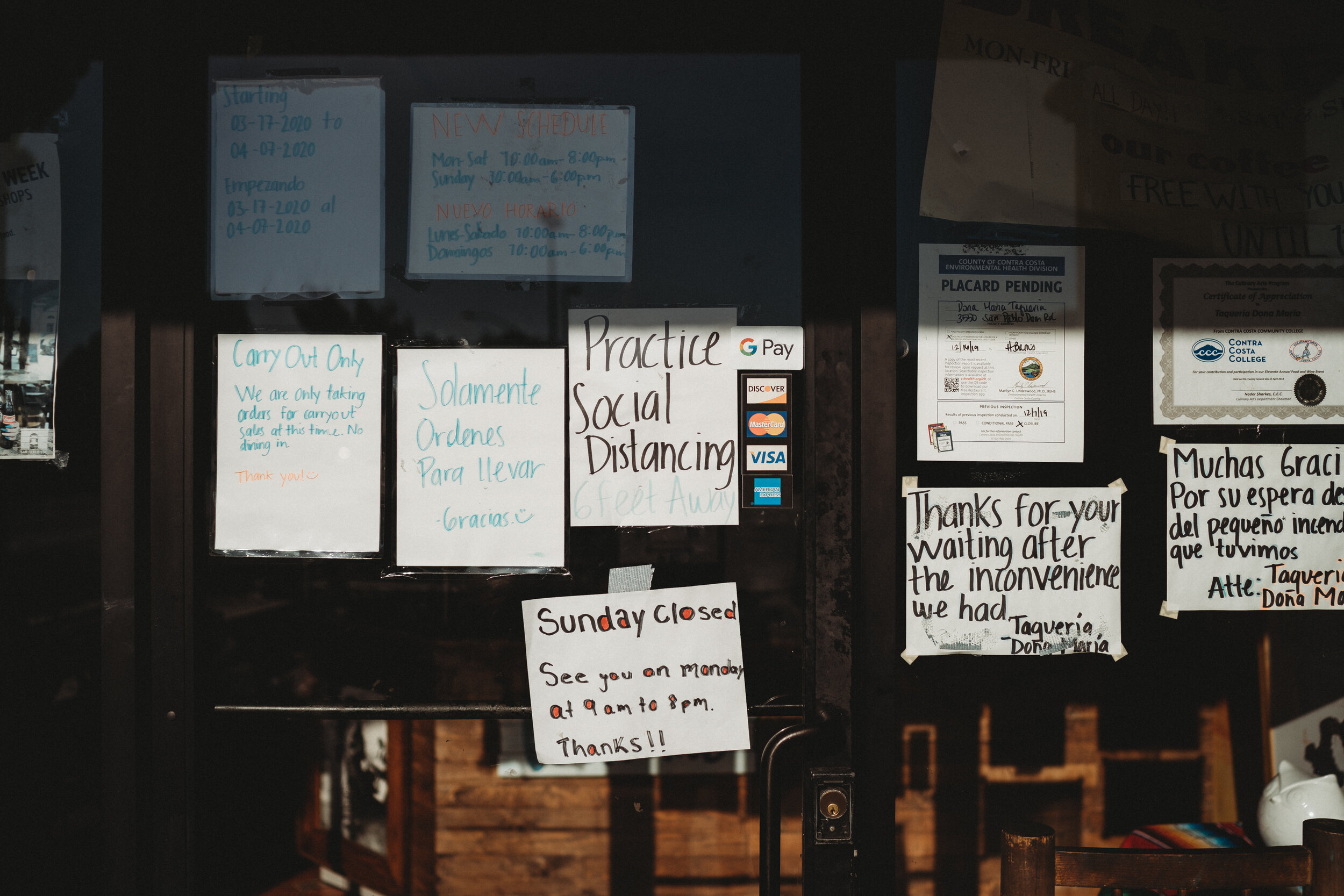

The pandemic has been particularly challenging to business owners whose first language isn’t English, and who have been thrust into the “essential” category without accessible information. It's difficult to interpret and enact new safety measures even without a language barrier. Many immigrant shop owners have relied on their children or community for help navigating the ever-changing news. Meanwhile they’ve remained on the frontlines.

Next door is the gas station, and for a moment, I wonder: should I bring my camera in? Why would a gas station attendant want to talk to me, anyway? I am immediately proven wrong. The young attendant Dipreet and his uncle Saragbet are welcoming, even if it’s hard to convey the purpose of my project. Natural window light does not discriminate against gas stations, and a Plexiglass sneeze-guard really adds to the apocalyptic nature of this photo series.

I stop quickly at one of my town’s Indian grocery stores, Paramba, before heading home. As with most stores in town, it doesn’t look like much has changed inside, besides the occasional sneeze-guard or box of gloves. Here, the only evidence is a bottle of hand sanitizer and a mask pulled up when a customer comes in. Paramba also sells some fashion items and cookware, but I gravitate towards the snacks, most of which I haven’t encountered before but very much want to try.

Owner Parangit is warm but a bit skeptical until her gregarious brother Indergit steps in. He directs the shoot, acts like he doesn’t want to be in the photos, and then completely hams it up in front of the camera. It’s hilarious, and a moment of encouragement during the strangeness of my trip. My camera agrees, and I come to accept the situational beauty in the fluorescent lighting.

Over the course of my project, three dry-cleaners, a used car lot, the most photogenic cobbler, and several other businesses politely decline to be interviewed and photographed. A locksmith with lights and music on never answers my knocks on two separate attempts. I don’t blame any of them; having a 50% acceptance rate is actually far higher than I expected.

But there are lots of highlights amid the moments spent meeting and talking with community members and business owners. El Sobrante Cyclery owner Ken, who has worked at the shop for 35 years, now has the additional job of informing customers that masks became mandatory this morning. Dr. Singh, a veterinarian, prefers not to remove his face mask for photos, but poses adorably with his mismatched dogs once they finish greeting me. Bakery worker Alex, donut shop owner Kathy, even Sabrina—the photogenic pawn shop employee who looks like she had advance warning of a photographer coming by—are all generous with their time, despite the surreal conditions of everyday life.

Today’s destination is Bottles: a hybrid Indian grocery store, sari shop, secret bar, and craft beer retailer. I walk into the sounds of a prayer tape coming from an old desktop computer behind the counter, interspersed with conversations between customers and staff members.

I began dropping by this spot last year, and I still haven’t gotten over the joy of walking out with a local sour beer and a pack of chana masala spice blend for the night’s dinner. I can’t leave without buying something new-to-me each time I visit—who knew there were so many ciders?—and my haphazard picks pretty much always pay off. Bottles even stocks East Brother Beer Company, based locally in Richmond, and one of my favorite breweries in the Bay Area.

I speak at length with owners Daljit and Kamaljit about the long-term economic effects of this shut-down. Supply chain issues have blocked rice deliveries, among other things, and Daljit is left with the task of keeping the shop stocked affordably while unsure of what will arrive through his doors. If all else fails, he said he’d even transition into donating whatever food comes in, if his clientele need it.

Luckily he still has a steady flow of customers, many loading up car-loads of bulk items. He also runs the restaurant Punjabi Kitchen out of this space, which is one of my favorites in town, and has stayed open for takeout throughout shelter-in-place. Even though I have to keep moving, I can’t turn down the warm chai that they offer me. I didn’t know I could love this store more.

After I leave Bottles, it takes me a minute to register what’s happening next door: a drive-through baby shower, complete with music and balloons and piles of pink-wrapped presents. Mama-to-be Kristy is thrilled to pose for photos, as is her friend LaTona, owner of Get It Girl Fitness (upon my arrival, she takes full credit for hiring a professional photographer for the event).

“There is a lot of camaraderie and comfort that is lost behind a mask.”

The party is in front of the newly opened fitness studio—the culmination of so much hard work closed to the public just months after opening. LaTona had adapted by loaning out all of her workout gear before closing up shop, and is now teaching classes virtually. The background situation may not be happy, but this celebration is—for a moment, you almost don’t notice that it’s held in a parking lot, or that the party favors are homemade face masks handed through open car windows.

As with most conversations these past couple of months, my dialogue with LaTona soon turns toward economic survival. Did you have to lay off employees? Any luck applying for loans? Even as we discuss the difficulties, she has no complaints: mainly, she empathizes with customers who can no longer afford personalized services. For undocumented workers who can’t receive aid despite years of paying taxes. For those who are balancing childcare, canceling weddings, working at hospitals. Despite being physically distanced, I have never felt so many commonalities with every person I meet.

“The background situation may not be happy, but this celebration is—for a moment, you almost don’t notice that it’s held in a parking lot, or that the party favors are homemade face masks handed through open car windows.”

I missed a few spots. I might go back. My favorite, talkative liquor store owner was not at his shop, for once. My husband’s go-to taqueria had a long spaced-out line at lunchtime. The auto repair shop wasn’t quite as tempting as going home and eating lunch.

One upside: I’ve never felt more connected to the people in my community. I look forward to the time when neighbors aren’t potential disease vectors, when supporting a local business doesn’t feel like putting anyone at risk. We might be months or years away from handshakes with new friends and hugs with old ones, but until then, I can’t wait for the delight of small interpersonal milestones to come.