Fuller’s Brewing Director John Keeling’s office door is open. Behind it hangs a white laboratory coat, a tie emblazoned with griffins, and a tour poster for iconic Manchester post-punk band, The Fall. A cabinet sits stacked with bottles of Fuller’s Vintage Ale, some over twenty years old. Boxed files of recipes and records—interspersed with bottles of beer from breweries around the world—burst from the shelves of bookcases. On the wall is a painting of Manchester’s Old Trafford Cricket Ground.

“When I entered the brewing industry, everyone in operations who wasn’t on the ‘shop floor’ wore a white coat,” Keeling says, smiling in the midst of his own joke. “Before that, brewers wore bowler hats, I believe.”

Fuller, Smith & Turner—known colloquially as Fuller’s—was founded in 1845 by John Bird Fuller, Henry Smith, and John Turner. The three men were linked to the business of brewing through either direct experience or their financial investments, and descendants of Fuller and Turner continue to have a role in the leadership of the brewery today.

Brewing has taken place near Fuller’s site on the River Thames for more than 350 years. The Griffin Brewery opened there in 1828, and was partly owned by John Bird Fuller’s father. Fuller Jr. took it on with the help of his business partners and formed a new brewing company. It’s the griffin that embodies Fuller’s identity, and the brewery bearing its name remains the source of every drop of Fuller’s beer to this day.

Fuller’s is London’s oldest independent brewery. Moreover, it has maintained both its independence and reputation as one of the world’s best brewers across nearly two centuries of industry turmoil, contraction and revolution. John Hall often cites the brewery as the inspiration for Goose Island. Without Fuller’s, ESB would not exist. It is a brewery that holds the answers to all-too-frequently unasked questions.

“Fuller’s form an anchor to quality and tradition, but also continue to demonstrate innovation and change at all levels.”

The short walk to the brewery from Stamford Brook station in West London takes you back in time on a gradient so gentle, you barely notice it’s happening. First you’re drawn back into the 1980s, with economically-secure young professionals wandering from café to fromagerie to wine bar without a care in the world for their credit score or student loan payments. Then you’re into the 1950s, with gap-toothed rows of houses that were too near the former naval shipyards for their own good, falling to stray bombs during the Blitz. After that, a gentle stroll through scenes of peaceful, pre-war English village life: neatly trimmed privet hedges, evenly spaced trees, children kicking a ball around, neighbors waving hello. Was that a vicar on a bicycle?

Turning onto a busy road with multiple lanes of traffic slightly dispels the illusion of a village, but then the familiar aroma of mashing in reaches your nostrils. Familiar, and yet not, for there’s an intensity to this bouquet of barley that speaks to Fuller’s reputation. It’s not just the soft, syrupy note of lightly kilned malt, but sumptuous, rich layers of warming, cake-like sweetness—an aromatic aria sung by Maris Otter.

Impossibly hidden until the last moment by leaning, verdant trees (who love seeing the look on people’s faces), Fuller’s is suddenly unveiled: vast, Victorian and postcard-poised. You are very much here now, not where—or, indeed, when—you were before. The time portal closes behind you.

On the corner, the dually-named The Mawson Arms/Fox and Hounds is what many visitors see first, presenting itself as a sort of mental bookmark for the last thing you’ll be doing on your time-travel holiday. Noted poet Alexander Pope once lived in this building, perhaps when he was working on his translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey. A misunderstanding of local licensing laws by one of the pub’s many landlords resulted in the pub’s double moniker (licenses for the sale of wine and spirits being registered separately to the one for beer), though many simply refer to it as the brewery tap.

The Griffin Brewery itself, a fortress of greenish-grey stone walls and iron gates, spirals outward with its oldest equipment and facilities interwoven amongst its newest: concentrically-ringed towers and temples of iron, copper and steel like the core of some fractal, industrial organism. Enormous red trucks in the brewery’s livery are loaded and unloaded all day, as tour groups are escorted in their high-visibility-jacketed flocks from one building to the next.

Behind the brewery, the River Thames flows, and once would have brought boats of grain to Fuller’s for its on-site maltings, which was eventually destroyed by bombers in the Second World War. Back around the front, on what used to be the Head Brewer’s cottage, grows the oldest wisteria plant in the UK, brought here as a cutting from China in 1816. Terraces of houses lining the brewery that were once worker accommodation are now sales offices. Older shells are repurposed for housing new life and new functions. Like the wisteria, Fuller’s has grown deep roots into its surroundings and found room to grow in a finite space.

On our tour of the sprawling, original brewhouse, Keeling recalls, offhandedly, working on its mash tun, which resembles a brick-clad silo used for launching Jules Verne’s men to the Moon. It was installed in 1863. The original copper brewing kettle is even older, built in 1823, before Fuller, Smith, and Turner took over. The two malt milling machines are practically youngsters by comparison, dating from 1932, requiring no more maintenance than having their rollers replaced “every 20 years or so.” They remain in use to this day.

Everywhere in this living museum are signs of not just life, but labor. Wooden staircases have grooves worn by the boots of hundreds of brewers. Discernibly fresher layers of paint cover the favored parts of handles and bannisters. An extensive, winding forest of various generations of conditioning and maturation tanks is accompanied by stories of generations of brewers improving on their predecessors' work. Everything has seen the touch of working hands and been passed on to others.

The contrast with Fuller’s modern 320-BBL (446 U.S. BBLs) brewhouse couldn’t be more stark: the kind of gleaming, multi-vessel behemoth spotted in many large breweries, all seemingly controlled by a man in a booth via several screens. All of this lies just beyond the original brewhouse, and there’s a sense of transgression in peering behind the curtain to see it, even though it forms part of tours for the public. It’s still Fuller’s, just a more realistic version. With breweries this old, realism isn’t what we want to see.

This is a brewery certain to provoke emotional responses, and the age and sheer gorgeousness of it fogs the lens needed to measure it. Conversely, to attempt to unpack everything Fuller’s is with mere data is just as problematic. The brewery is 173 years old, with an estate of nearly 400 pubs as well as an import, export and distribution business, brewing 337,000 BBLs (470,000 U.S.) a year, using 6,500 tons of barley annually and filling up to 10,000 casks a week. Fuller’s is less of a factory where a beer is made, and more the heart of a living network of history.

This concept is something of which Keeling—a fan of The Fall, a band famous for its post-industrial brand of magic realism—is all too aware.

“Frank Zappa said you aren’t a real country unless you have a beer. Well,” he says, smiling again right before the punchline. “I say you aren’t a proper brewery without a brewing philosophy.”

Manchester-born John Keeling joined Fuller’s in 1981, rising through the ranks from Junior Brewer to Brewing Director and Fuller’s Ambassador. His many achievements include the release of the highly acclaimed Brewer’s Reserve and Past Masters series, the installation of a £2 million ($2.75M) filtration and centrifuge system, and the recent multi-collaboration collection Fuller’s & Friends (which paired brewers from Fuller’s with six different UK craft breweries to create a pack of unique beers to be sold in a national chain of supermarkets).

“Craft brewers can innovate faster than we can. But what they don’t have, is a past. So why don’t we make the past count?”

It quickly becomes apparent that Keeling has an anecdote for almost every room and item in the entire Griffin Brewery. However, there are almost just as many anecdotes about the man himself. James Kemp, former Head Brewer at Marble and now in the same role for Yeastie Boys, once worked at Fuller’s in quality control.

“I remember [Keeling] trolling the other brewers in a very quiet fashion one day,” he says. “He'd been on a trip to Belgium and had brought back a whole load of sours for tasting. He didn't tell them what they were, and these lads were mid-4% cask drinkers only. There were many and varied sweary exclamations as they all spat their tasters out, while John was chuckling to himself.”

Whilst his days of wearing a white coat are over, Keeling remains key to directing the brewery’s output and culture, even as the summer of 2018 will see his official “retirement.” Whilst he will be leaving Fuller’s, he has just been elected chairman of the London Brewers’ Alliance (LBA) and will be reviving its role as a festival organiser, with a new LBA event being hosted at Fuller’s in June. He believes that the absence of white coats from the modern brewer’s wardrobe speaks to the change in the entire industry.

“With the advent of craft beer and the new people entering [these roles], they didn’t come up the formal way,” he says, referring to the craft sector’s penchant for self-tuition. This doesn’t seem to be a criticism though. That, as it turns out, Keeling reserves for marketeers in the mid-20th century.

“When marketing got involved [in the direction of breweries], there was a change in the philosophy of brewing.”

The topic of philosophy, good or bad, is one to which Keeling frequently returns. Marketing switched the focus of brewers from exploring flavor to, in his words, pursuing “the most neutral liquid possible, as cheaply as possible.”

That pursuit was where Keeling began his brewing career, at the Manchester brewing plant of Watney’s, an (in)famous name in British brewing history. Its notoriously bland Red Barrel Ale, available in hundreds of Watney’s-owned pubs across the country, was a ubiquitous reminder of the decline of traditional brewing practices and cost-cutting. The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) was formed in response to the increasingly prevalent “neutral liquid” being produced by brewers like Watney’s, who favored stable, sterile keg beer over traditional, cask-conditioned beer.

“We were making beer with only 40 percent barley, using buckets of enzymes to effectively convert the sugar,” Keeling recalls. “We had to wear gauntlets and protective equipment. I remember thinking, ‘This is strange, that we’re adding something to beer that we’re too afraid to splash on our skin.’ How natural is that beer?”

Keeling laments cost-cutting as the objective of brewing science and skill with a genuine sadness. “That’s not the way of the craft beer revolution,” he says, and to him it really is a revolution, and a new period in history.

Fuller’s is London’s oldest independent brewery. Its biggest hometown rival, Young’s (founded 1831), departed the capital in 2006 and is now owned entirely by Charles Wells in Bedfordshire. Aside from the Budweiser and Guinness plants that popped up in the capital, brewing was by no means a booming industry in 20th century London.

In fact, the revolution Keeling refers to didn’t truly take root in London until the opening of The Kernel in 2009 and Camden Town Brewery in 2010. These very different—and, more importantly, extremely non-cask-focused—breweries heralded the beginning of something new.

Thanks to the inspiration provided by those early pioneers, the floodgates truly opened in 2012. There are now 109 breweries in London, with at least another dozen in the active planning stages at the time of writing. To put it another way: every single operating brewery in London was born more than 150 years after the founding of Fuller's. Some might call that a generational divide.

Perhaps understandably then, like many of its peers, such as Young’s, Marston’s, Shepherd Neame and Samuel Smith’s, Fuller’s did not at first seem fully comfortable with, or even fully aware of, the change that was coming. Continuing to trade on its traditional, family-owned, big brand credentials, it would be a while before Fuller’s began to interact with and participate in the new craft beer culture.

“Frank Zappa said you aren’t a real country unless you have a beer. Well, I say you aren’t a proper brewery without a brewing philosophy.”

Whilst the company as a whole seemed slow to adjust to the new conditions (not to mention figure out how to reap the benefits), Keeling grasped what was happening almost immediately.

“It’s made flavor more and more important. The brewers have become the most important people in the brewery again, not the marketeer, not the accountant,” he says. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he is happy for UK breweries to pursue American influences, but thinks there are still missed opportunities. “I wish they would go a step further than the American versions, and look back at the roots of it, which is the British brewing tradition, and see what they can do with that!”

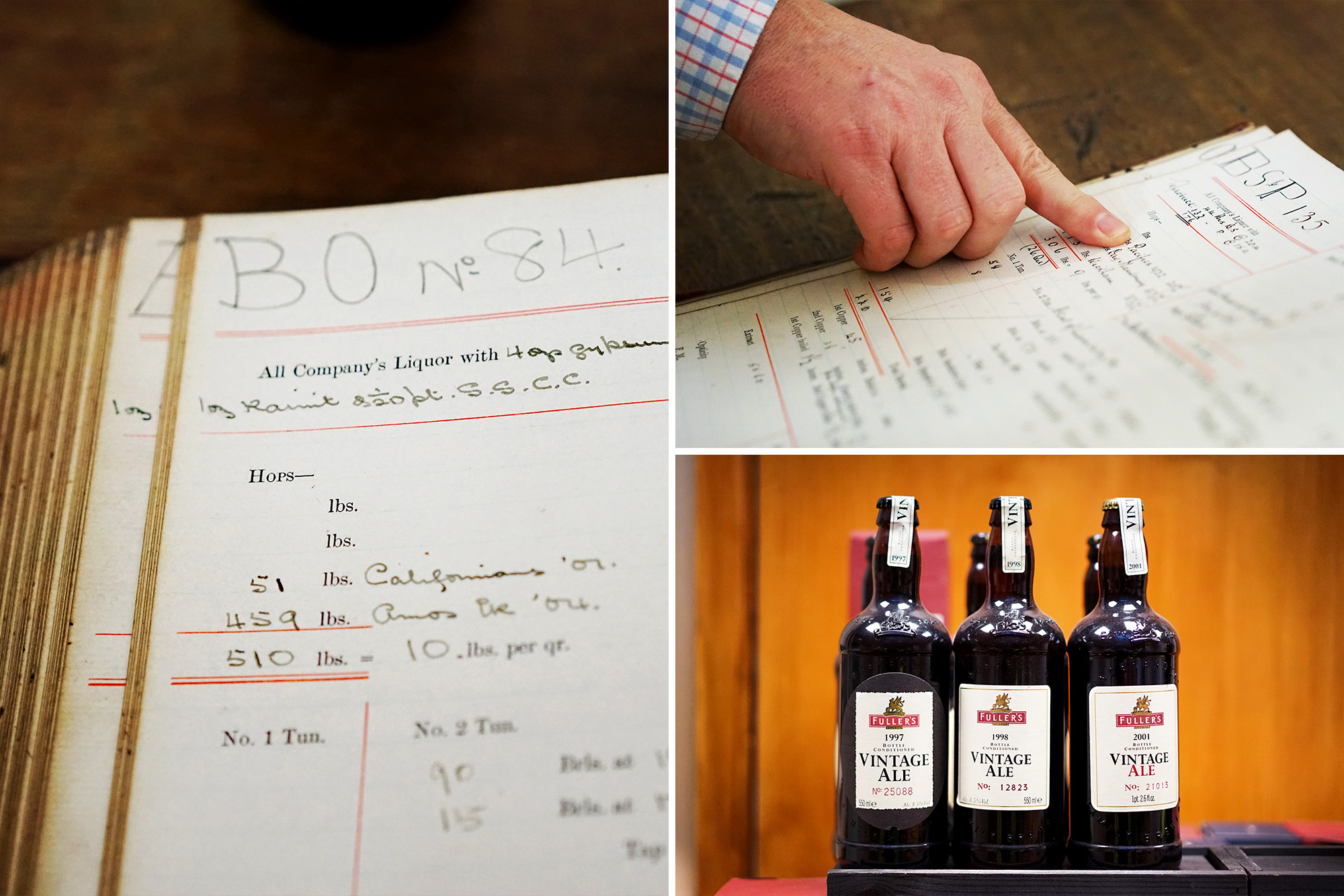

British brewing history is another subject close to Keeling’s heart. The lack of appreciation of it, perhaps due in part to that vast generational gap, frustrates him. He points at an open page from one of the brewery’s recipe books, proving that Californian hops were being used in Fuller’s beers at least as far back as the 1900s, and hops from Oregon in 1891.

The motivation behind the Past Masters Series, using recipes from these archives of Fuller’s brewing history, seems obvious to Keeling: “Craft brewers can innovate faster than we can. But what they don’t have, is a past. So why don’t we make the past count?”

And yet, the brewery is seen as classic instead of cool. Perhaps that’s because its core range of beers covers a range of solid, dependable, drinkable styles that have finesse that experienced drinkers crave, if not the flash that attracts new fans.

While some drinkers might not be paying attention, some breweries certainly are. Dan Lowe is the co-founder of Fourpure Brewing Co in Bermondsey, South London. The brewery—which he founded with his brother Tom—and its notable recent growth hints at Fuller’s-sized ambitions.

“Fuller’s form an anchor to quality and tradition, but also continue to demonstrate innovation and change at all levels,” Lowe says. “They showcase guest beers in their pubs and they support breweries on technical projects such as laboratory analysis.”

Fuller’s bread and butter is, perhaps unsurprisingly, not IPA. London Pride, a “Premium Ale” “Best Bitter,” or “Traditional English Pale Ale,” depending on which decade’s marketing copy holds sway, is the company’s flagship beer. Originally launched in the 1950s to be the upmarket alternative to its Ordinary Bitter, it was, according to brewery lore, named by a member of the public and refers to the local name for a flower. Saxifraga × urbium is a hardy perennial which grew wild and thrived amongst the bombed ruins of London during the Blitz. The flower became an everyday symbol of the resilience of Londoners against attack, one all the more poignant in London’s present.

The beer itself captures a lot of the brewery’s strengths: rich grain character, floral, herbal hop notes from English varieties Challenger, Goldings, Northdown, and Target, and a distinct fruitiness from the house yeast strain. Its ubiquity across casks, kegs, cans, and bottles in London reflects its adaptability as a recipe.

Fuller’s second biggest seller is a far more recent invention. Frontier, launched in 2013, is the brewery’s sincere stab at a craft Lager, though it actually has more in common with an American-brewed Kölsch, being brewed with the brewery’s house ale yeast strain and hopped with Liberty, Cascade, and Willamette.

Fuller’s Extra Special Bitter (ESB), meanwhile, is the origin of the style—the literal first ESB in the world. Keeling sees ESB as something not hugely different to IPA—a hop-forward and higher-strength amber beer, but with an identity of its own. The glory of it is best appreciated in cask-conditioned form, where its otherworldly deep malt structure and leafy, peppery hop profile sing in a harmony of marmalade and spice notes.

This is just a handful of the deeply accomplished beers the brewery is known for. Fuller’s might not get the same kind of hype or adoration given to younger breweries like Beavertown or Cloudwater, but it is a brewery about which many UK beer fans have strong feelings. Very few people will linger on an online shop on their lunch break for Fuller’s, or queue up at 10am for Fuller’s for example, but almost everyone has a favourite Fuller’s beer and a preferred method of dispense for it.

“Fuller’s were doing craft before craft was a thing, quietly producing flavourful and aromatic quality beer, and had a barrel aging programme before it was de rigueur. They were ahead of their time,” Kemp says. “They understand business realities, too. I think a lot of breweries could learn a bit from them.”

Dominic Driscoll, brewer at Thornbridge and another Marble alumnus, concurs. “There are over 100 breweries in London now and very few of them have any experience or formal training, let alone anything that could be perceived as brewing heritage. Fuller’s are a bastion of quality, from brewing, to the way they train their pub staff, to how they look after their beer.”

It’s those credentials that left many industry observers quietly pleased with the news that Fuller’s had bought a 100% stake in Sussex-based Dark Star Brewing Co earlier this year. While similar purchases often leave beer consumers and professionals alike feeling cold, there was a sense that both preservation and growth would go hand-in-hand for Dark Star.

The Fuller’s & Friends series brought Fuller’s together with six breweries (Cloudwater, Fourpure, Hardknott, Marble, Moor, and Thornbridge), all brewing distinctly different beer styles under the same roof, and packaging them for sale as a six pack to a national chain of supermarkets (Waitrose). It was the rare endeavour that got the attention of craft beer geeks and traditional ale fans alike. Minor Twitter frenzies broke out as people discovered the beers had landed in their local stores. It was probably the closest Fuller’s have come to experiencing modern-day beer hype.

As far as Keeling is concerned, there was a benefit beyond just making six exciting new beers—a Lager, a Saison, an ESB, a Red Rye Ale, a Smoked Porter, and an NE IPA. “We sent six different Fuller’s brewers to six different breweries [to pilot brew the recipes ahead of brewing them on Fuller’s main kit], and they came back with a new enthusiasm and new ideas. It’s fantastic.”

The masterstroke was to involve the retailer from day one of the project, ensuring a route-to-market for these beers beyond Fuller’s pubs and online shop, but also far beyond the current retail footprint of many of the partner breweries. Waitrose is a chain of supermarkets perceived as upmarket by most consumers, and is also the food retail division of John Lewis, the largest employee-owned retailer in Britain. It also happens to have arguably the best craft beer range of any British supermarket.

It wasn’t smooth sailing, of course, as expectations on all sides had to be met. And while Fuller’s is a large brewery, it isn’t necessarily flexible. However, it was evident from the early stages that they were committed to make it work.

“Fuller’s came to that meeting on the basis it would be a six-pack of 500ml bottles,” Fourpure’s Lowe say. “Yet when the group of collaborators quietly expressed that 330ml was where we should be, John embraced the change and set the technical challenge to the team.”

Keeling likes to imagine older and younger drinkers sharing beers out of this pack, and while it might seem a little corny, that’s clearly what was happening on the various collaboration brewdays. It was also clearly an experience, and a challenge, enjoyed by the brewers involved.

It’s also telling that each brewery jumped at the chance to be involved. It’s unlikely the same would be said if, for example, Marston’s or Shepherd Neame had come calling. As the words of industry colleagues demonstrate, Fuller’s occupies a unique space in the hearts of professional brewers that many of its older-school contemporaries do not. The chance to work with Keeling himself was obviously also a crucial factor. However, while he remained a driving force in bringing the project about and adding his weight to getting the deal done with Waitrose, it’s clear that Head Brewer Georgina Young and her team of brewers were the ones left to take the lead on executing the project.

“I’ve always been quite good at delegating,” Keeling says. “I think the reason a lot of people stay, and I why I’ve stayed, is because we’re always given new things to do.”

Hayley Marlor joined Fuller’s in 2012 as part of its Graduate Scheme, after completing her Bachelor’s Degree in Biochemistry at Imperial College, London. She was proud to be part of the brewing team tasked with Fuller’s & Friends, assigned to help brew the Marble collaboration and learn from Marble in the process.

“[Keeling] has a way of inspiring people with his vision, and he supported and encouraged us all along the way,” she says. “He has always been approachable and his enthusiasm in all he does is infectious. Once I joined the family, I soon became aware of the ethos that anything is possible. Determination and ambition are rewarded with support and encouragement. There’s a real sense of involvement with the business and it’s great to work in an atmosphere like this.”

At lunchtime, over a pie and pint in The Mawson Arms, Keeling is talking about promoting a wide choice of beers across the Fuller’s pub estate. His philosophy in this area, like everything else, is pretty hard to argue with:

“You can only do the right thing and be fair to people.”

Fuller’s history, commitments to technical excellence and their treatment of their people are all things that younger brewers should admire and aspire to. But the brewery’s most impressive quality, perhaps, is how it sustains itself with a culture of its own—and with a future planned more than two moves ahead.

“Reg Drury, who became Brewing Director in December 1980, hired me on January 1, 1981, so his first ever decision was to hire me,” Keeling says. “The last thing he ever did at Fuller’s was to recommend me to the Board as his replacement, so I was his first and his last decision.”

The fact that this cohesive group of standards, ideas, and feelings can be referred to as a philosophy says a lot about Keeling, but also about the company that has employed him for 37 years. In craft beer, thanks to the industry’s lightning fast metabolism, each year can feel like a lifetime. In Fuller’s, we have a brewery that quite literally deals in lifetimes, because it feels responsible for looking that far ahead. Its employees serve not just as staff, but as caretakers for the continuity of something greater, and take responsibility and pride in finding successors who can carry the torch for the next few decades.

In Keeling’s own words, philosophies grow. Even those who leave Fuller’s end up continuing the growth of a culture in fresh soil, across a land far wider, richer, and more fertile than it has ever been. They walk back through those decades to the present, and then they take steps into a rewarding future.

“One of my first decisions as Head Brewer was to hire Georgina Young, and then I ended up recommending her as Head Brewer. She’s always gone onwards and upwards. I think she’s been pushing for it for a while.”

He smiles again.

“What I’ve learned from my predecessor Reg, was how good he was at spotting when people needed the next challenge.”